As explained in the first article of our series, tort reform has arrived in Florida with House Bill 837 (“HB 837”) being signed into law on March 24, 2023. Our first article discussed changes in the law relating to the statute of limitations and attorney’s fees. In this section, we will address the new standard for comparative negligence, admissibility of medical expenses, both past and future, and the potential impact of these changes.

Modified Comparative Negligence

Florida previously followed pure comparative negligence, which resulted in a plaintiff being able to recover damages even if the plaintiff was found to be at fault for the majority of the fault, based upon an apportionment by a jury. In such cases, barring limited exceptions, such as a statutory drug and alcohol impairment defense, a defendant could be held liable for damages even if the plaintiff was 99% at fault. Florida now joins the majority of jurisdictions in the United States in adopting modified comparative negligence. Over 33 jurisdictions currently use a form of modified comparative negligence. Please note that this new standard does not apply to medical malpractice actions.

As a result of the new law, if a plaintiff is more than 50% at fault, they cannot recover any damages. We anticipate that due to this change, in cases where a plaintiff is predominantly at fault, the case will either not be accepted by an attorney or alternatively, if it is, it will not reach the jury trial stage. Cases that pose the question of whether or not a plaintiff can overcome the threshold may be settled early on in the litigation process, or even pre-suit, to avoid the risks associated with them, to the extent that they are undertaken by attorneys. As a result, there may be more cases resolved at the pre-suit stage as compared to current statistics.

Admissibility of Past and Future Medical Expenses

Prior to HB 837, a plaintiff was permitted to board the full amount of medical bills charged for services rendered. The collateral source law did have exceptions for Medicare, Medicaid, and programs and benefits under Title XVIII and Title XIX; any federal, state, or local income disability act; or any other public programs providing medical expenses, disability payments, or other similar benefits, except those prohibited by federal law and those expressly excluded by law as collateral sources. However, the majority of the time, the exceptions were not triggered in many cases. All adjustments or reductions were made post-verdict via set-off for collateral sources. This resulted in common situations where a party would board bills much larger than what had actually been paid, resulting in the jury being under the impression that greater amounts were owed/incurred than the actual numbers.

With HB 837, the evidence that is permitted to be offered to a jury to prove damages for past medical bills that have already been satisfied is limited to the evidence of the amount actually paid, regardless of the source of payment. This is a very large turnabout compared to the prior law, as the entire amount of the bill would be presented to a jury. Of critical importance is that the initial billed amount is not admissible anymore.

For unpaid past medical bills, admissible evidence will depend on whether a plaintiff has health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, or other similar benefit programs. The key changes to the law are:

- If the plaintiff has health care coverage but obtains treatment under a letter of protection or does not submit claimed medical charges through available health care coverage, evidence of the amount that health care coverage would have been contractually obligated to pay to satisfy those charges is admissible.

- If a plaintiff does not have available health care insurance or has Medicare or Medicaid, evidence of 120% of the Medicare reimbursement rate in effect on the date of the incurred medical treatment or services is admissible. If there is no applicable Medicare rate for the services in question, 170% of the applicable state Medicaid rate is admissible.

- If there is no applicable Medicare rate, the evidence admissible is 170 percent of the applicable state Medicaid rate.

As such, the new law is that damages that may be recovered do not include any amount in excess of the evidence of medical treatment and service expenses that were actually paid or would have been paid under Medicare or Medicaid. Further, it cannot exceed the sum of amounts actually paid, amounts necessary to satisfy charges due and owing, and the amounts necessary for reasonable and necessary future medical treatment and services.

This provision should result in a more accurate picture being presented to a jury as it relates to past medical expenses. Further, this change may well discourage parties in litigation from seeking treatment from providers that only treat those in litigation and/or are known to bill well above market rate, for the purpose of creating larger monetary damages to present to a jury. Further, while some on the plaintiff’s bar would assert that letters of protection enable those without health care coverage to obtain treatment (which can be true), this is often a tactic that is used to increase damages in cases, with negotiations that occur after settlement and/or trial. Further, larger past medical bills could present a more severe picture of a case and, hopefully, a greater overall jury award. Over time, hopefully this change will normalize verdicts to be more in line with the evidence, the care received, and the severity of the injury rather than being based upon health care charges that are not reasonable, customary, or otherwise connected to the local market pricing.

For future medical expense entitlement, the “usual and customary” amount will also depend on whether a plaintiff has health care coverage. 120% of the Medicare reimbursement rate in effect on the date of the incurred medical treatment or services is admissible. If there is no applicable Medicare rate for the services in question, 170% of the applicable state Medicaid rate is admissible. The new law has made the following changes below for future medical expense damages:

- If a plaintiff has health care coverage other than Medicare or Medicaid, evidence of the amount that could be satisfied if charges were submitted, in addition to the portion of medical expenses covered under an insurance contract, is admissible.

- If a plaintiff does not have health care insurance or has Medicare or Medicaid, evidence of 120% of Medicare reimbursement in effect at the time of the trial for such future services is admissible.

- If there is no applicable Medicare rate for the services, the evidence admissible is 170% of the applicable state Medicaid rate for that treatment or service.

Prior to this change, evidence of what a benefits program might pay, whether it was group health care coverage or Medicare, Medicaid, or another, was not admissible for future expenses because such benefits were deemed uncertain and subject to change and/or availability. From a practical case-handling point of view on the plaintiff’s side, future medical care, if it is actually needed and sought, could be more challenging to plan for and to fund. It is likely that HB 837 will see litigation over the changes, and this is an area that is likely to be challenged by plaintiff’s attorneys.

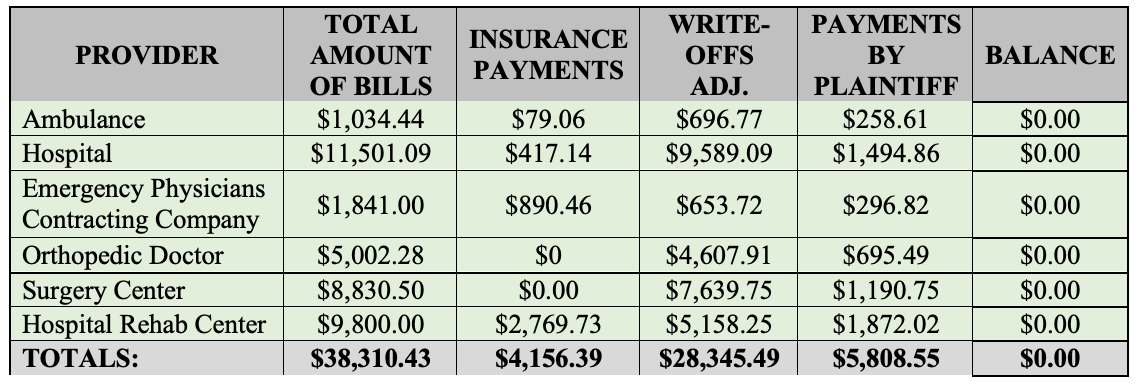

As an example, the following chart illustrates hypothetical gross medical charges in a personal injury case, including all charges, the insurance payments, write-offs, payments by the plaintiff, and the balance due. This example does not include any balances due or Letters of Protection as a point of reference.

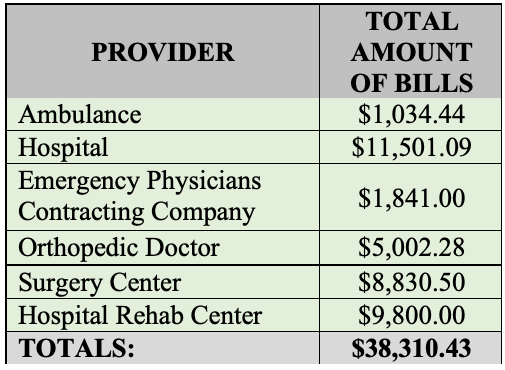

In the above chart, we will use this as an exemplar to show the new procedure. Prior to HB 837, in a case like this, the Plaintiff would possibly present to a jury a medical expense chart that might look something like this:

However, all reductions were done post-verdict prior to HB 837. Possible calculations, assuming all expenses were awarded would be as follows:

- Past Medical Expenses: $38,310.43 (the gross total)

- If all expenses were awarded, you would look at what the Plaintiff paid out of pocket and what insurance paid for the bills. Those two columns added up are $9928.94 for actual past medical expenses. There is an associated write-off for over $28,000 that would be taken off, post-verdict. You can see that in the primary chart as a reference.

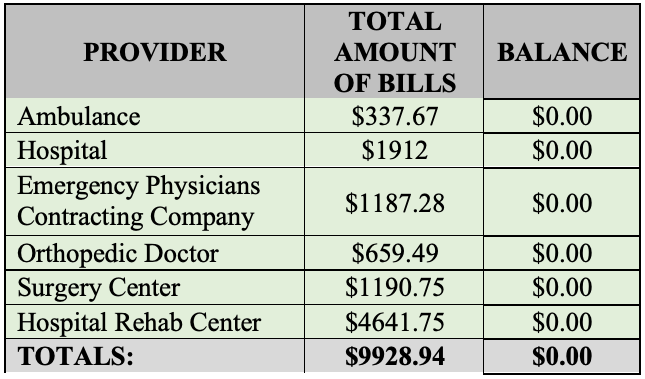

After HB 837, Plaintiff would instead present a modified picture of medical expenses, based upon what was actually paid and/or accepted by insurance/the provider. The law now results in a plaintiff presenting what was actually paid or accepted in the event that health insurance was used and/or cash payments. Please note that this example does not include Letters of Protection, which are discussed more below. Letters of protection and/or cases without medical insurance are likely to become more labor intensive. A possible medical expense boarding might now look like this for someone with health insurance and/or cash payments out of pocket:

As you can see under HB 837, the total presented to a jury is vastly different than pre-HB 837. A jury would get a sum for each provider, which consists of what insurance paid and what the plaintiff paid, which gives us the total medical bills. A party is no longer permitted to board medical expenses that were not actually incurred or paid. If insurance was used for the care, any balance due is likely not appropriate to be included, as balance billing is generally not allowed to be presented. Further, if a party was a cash payor and the balance was written off after accepting a reduced cash payment, that should not be presented either. The change in how past medical expenses are addressed should be very important in litigation and arguably, should result in jury verdict awards that are more closely tied to the actual case value, versus numbers that are not representative of what was truly incurred.

In cases where you have either a Letter of Protection and/or no health insurance, you will have to look to the Medicare and/or Medicaid rates, as noted above. However, the task of determining what those bills presentations to a jury should be is going to require going through each set of bills in a case. Next, you will have to look at what the CPT codes are to match those with what the rates would have been if not for the Letter of Protection/not using health coverage, and then one has to apply the permitted multiplier for either program, as noted in the new law. This provision of the statute is likely to create additional labor for both sides in a personal injury case.

There are likely to be disputes as to the correct codes, the amounts and issues when providers unbundle charges instead of keeping them bundled. In addition, this is an area where we may see a cottage industry of third-party service providers arise, to try to save time and billable hours in determining what the boardable amounts should be, rather than leaving the attorneys to resolve it. Many attorneys are not experienced in billing and coding, or navigating the databases for Medicare and/or Medicaid, to properly assess what the charges actually should be and to ensure accuracy. In addition, it is entirely possible that parties will have competing experts to opine as to what the bills presented should be using the Medicare/Medicare rate and the multiplier, leaving the trial judge to decide such disputes before presentation to a jury.

Generally, bundling refers to the use of a sole CPT code to describe separate procedures that were performed during an episode of care delivered within a defined period of time. Under the bundled payment approach, providers and/or healthcare facilities receive a single payment for all the services performed to treat a patient undergoing a specific episode of care.

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) defines unbundling as occurring when a “billing entity uses separate billing codes for services that have an aggregate billing code.” Unbundling can occur either by mistake or be done to increase payment. In personal injury cases, unbundling can be used as a way to increase the medical billings to be presented to a jury. It is always on a case-by-case basis as to whether a procedure can be unbundled and depends on the treatment rendered. In example, if an incision is a necessary element of a surgical procedure, that is not a separate procedure and should not be its own CPT code. Similarly, closure of the incision after the surgery is complete, is not separate but part of the surgery as a general rule. If a surgery was performed, but the incision and closure were coded separately, that would be potential unbundling.

Unbundling occurs when multiple procedure codes are billed for a group of procedures that are covered by a single comprehensive code. Unbundling could apply if the other procedures required additional skill and time required to perform. For example, if the closure of the surgical incision required an extensive amount of time and skill, these additional services may be unbundled or reported using individual codes along with an appropriate modifier.

Given the highly detailed and fact specific nature of care in every case involving damages, it is likely going to be a more complex task to calculate past medical expenses under a Letter of Protection and/or in a party without health coverage now, as it will require an analysis of the billings, codes, and assessment of the reimbursement rates. This will be an area of the law that likely will take some trial and error, to address the issues in the most effective way possible.

For more information on these topics or related matters, please contact Elizabeth Tosh, elizabeth@zinoberdiana.com, 813-642-4229.